Press

British journalist Melanie Grant offers a glimpse into the rarefied world of high jewelry by explaining the historical and artistic importance of some of the world’s most innovative pieces in her new book, Coveted: Art and Innovation in High Jewelry (Phaidon).

The 208-page publication was just released in the U.K. and Europe and will appear in the U.S. on November 11. It profiles more than 75 of the world’s leading high jewelry artists and brands, including Boucheron, Bulgari, Cartier, Chopard, Cindy Chao, Hemmerle, James de Givenchy, Van Cleef & Arpels, Victoire de Castellane and Wallace Chan. Grant, luxury editor of The Economist’s sister publication 1843, discusses their conceptual approach, materials, quality of design and workmanship, revealing what makes these creations not only coveted objects of exceptional value but also works of art.

The book is separated into five chapters: Modernism; the cultural exchange between East and West and its effect on design; the evolution and meaning of innovative materials; the natural world as inspiration; and the growing empowerment of women, as designers and consumers.

Coveted reveals high jewelry’s evolution and increased association with the world of art. From heritage brands Fabergé and Cartier and their connection to Art Nouveau and Art Deco, to Salvador Dalí’s collaboration with Verdura and more recently, Scandinavian brand Georg Jensen, who created sculptural cuffs and rings with Zaha Hadid. In addition, the book charts the changing nature of high jewelry collectors – from royalty; to wealthy industrialists in the 20th century; and today among new, younger global elite.

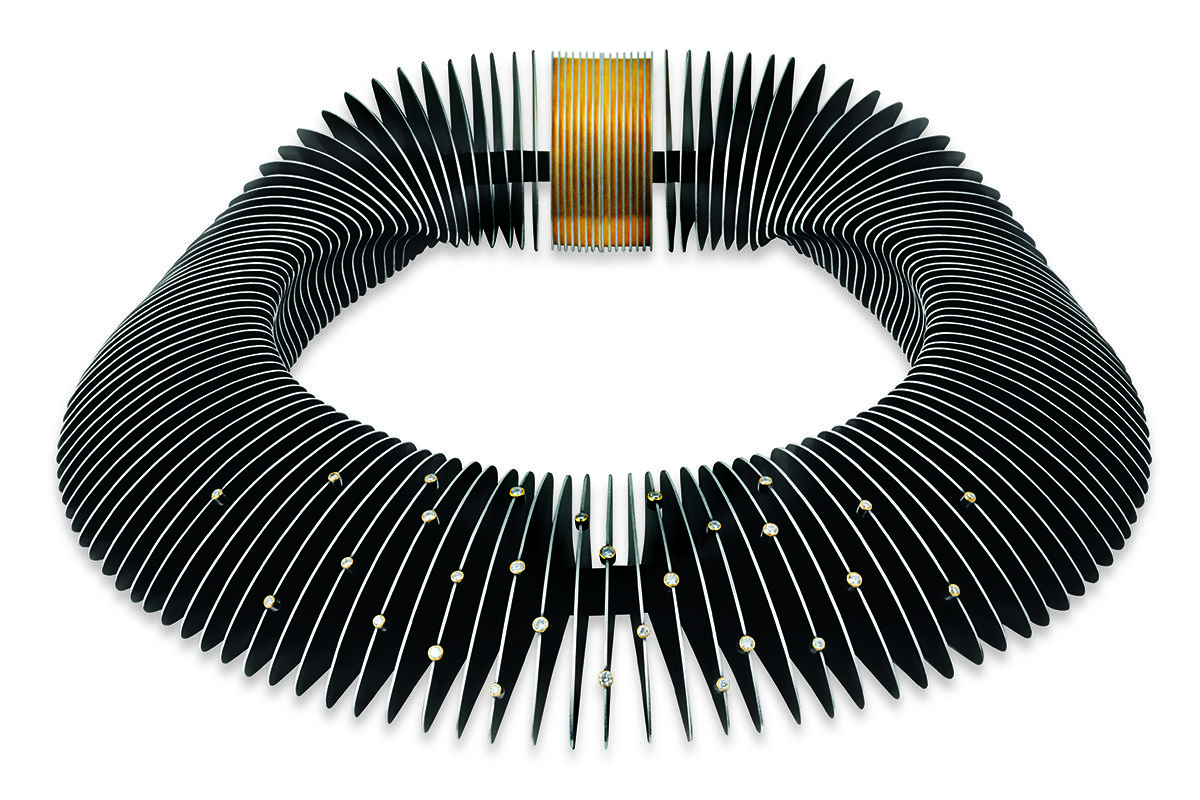

The book includes approximately 190 colored illustrations with captions listing the materials from which the object is made. This includes innovative combinations of precious metals and stones with hi-tech industrial materials such as titanium and carbon fiber favored by several contemporary jewelers.

Recently, Grant responded to a few questions about her new book by email. The conversation is below:

My book is essentially asking the question ‘can jewelry be art?’ When I started writing about jewelry for The Economist around seven years ago I was often taken aback by the way it was prevented from entering the art space at some exhibitions, art galleries and shows. I’m not talking about fine jewelry you buy on the high street but one of a kind high jewelry, conceived and created by artisans over a number of years to celebrate a concept or idea. Unless it was made by a fine artist it was often dismissed and as I got deeper into my obsession with high jewelry, as I saw more work by high level contemporary designers it made me question the hierarchy of art. Why was a painting or sculpture at the top and a jewel languishing lower down? Were the economics at fault? The fact that intrinsic value is so integral to the identity of the materials involved such as diamonds and gold might have played a part or was it historical? I tried to find reading material on the subject but couldn’t find anything substantial challenging the status quo so when Phaidon asked me if I wanted to write a book, it seemed the natural choice.

I’ve collected jewelry for about thirty years. I started off in flea markets as a teenager and graduated to antique silver in my twenties, then costume in my thirties and now I love modernist contemporary design in my forties. It’s lethal as a hobby because my taste is so wide. I like simplicity but also big ‘chi chi’ numbers which I could never possibly afford but just seeing a phenomenal Etruscan cuff by Van Cleef & Arpels or a pair of free floating diamond ear clips by Viren Bhagat makes me feel alive and somehow I found the right job to feed my addiction. The interesting thing is that as I get older I like bigger jewelry because I think I’ve become more confident in my taste, settling into a style that I’m unapologetic about. I like the fact that jewelry is accessible and inclusive despite its reputation to the contrary because there is something for everyone whatever your budget. It represents such a marvel of the imagination on all fronts.

Yes. To set jewelry free and to honor its ability to be art we have to do three things.

1. Acknowledge the fact it can be art at the top level by allowing it into museums, galleries, exhibitions and institutions dedicated to art.

2. Encourage jewelry designers to aspire to create art and when they do to describe it thus rather than calling it ‘product.’

3. To disregard the hierarchies that exists between the fine and decorative arts.

To admire it we have to love it for more than the price of gold or value of the stones because it’s true value lies in the artistry.

On the one hand we have the rise of the industrial, such as Fabio Salini’s carbon fiber or Michelle Ong’s use of titanium coupled with beautiful stones as an innovative combination and use of materials. When Wallace Chan created porcelain five times stronger than steel and Hemmerle swopped gold for iron in their design we witnessed a new type of precious. On the other hand the promotion of meaning or conceptual jewelry is key to innovation today and this is where jewelers can learn from fine artists. A jewel has to have more than beauty to be art so I would say that the escalation of meaning is the real innovation.

Rather than an era I’d say certain designers have changed design with radical creativity. Suzanne Belperron in the ’30s and ’40s, Jean Schlumberger for Tiffany in the ’50s, Andrew Grima in the ’60s and ’70s and Joel Arthur Rosenthal in the ’80s and ’90s. Today we have mavericks such as Ilgiz Fazulzyanov, Claire Choisne for Boucheron and James de Givenchy for Taffin. Every era offers us something different and I think the measure of great design is that it doesn’t date; it’s timeless but representative of history in that moment. It is tempting to say that design at the time of Rene Lalique during the Art Nouveau period for example was somehow more important than say a designer in New York today but the beauty of contemporary design is that one has to judge it completely on merit because we have no concept of how pivotal it will become and that’s rather beautiful in my opinion.

High jewelry is usually big and sculptural so cuffs, bib necklaces, tiaras and brooches allow that scale to really sing.

Cartier for example has the Tutti Frutti necklace first designed in 1936, which has carved emeralds, rubies and sapphires that resemble boiled sweets and that is still in demand. The sautoir, a long necklace coveted in the 1920s is still popular, as is the chandelier earring. The biggest difference now of course is that high jewelry isn’t just reserved for nobility but tech millionaires and business moguls are buying who are less hampered by tradition so the design of high jewelry is less conservative. Women are also buying for themselves in greater numbers than ever before and they eskew pretty, predictable design for bolder more unusual pieces. Collectors in general are cross collection high jewelry and fine art, partly encouraged by the auction houses who are taking jewelry more seriously and partly because jewelry design at the pinnacle is becoming more interesting.

It wasn’t easy. There are so many design houses I wish I could have included but it really came down to a feeling.

Having seen some of the best jewelry in the world over the last decade, I chose those I felt had elevated design to an art form just by being in the world. I’ve got big emeralds by Bina Goenka as well as a bronze eye sculpture by Maggi Hambling. I don’t discriminate. Much of the book is about power and how jewelry expresses that economically, socially or artistically and I wanted to honor the creators of what will become artifacts of the future.

If I gave you a name I’d have to leave town!

If this book achieves one thing I’d like high jewelry to be given more respect. Because of its beauty we often don’t take it seriously but we should. It is art at a certain level and I’m on a mission to get it recognized as such. I hope we can put our obsession with money aside and see its true value.

Image: Diamonds in extruded silicone, gold, and oxidized silver with magnetic clasp. Picture credit: Courtesy John Moore (p.118)

Original article: www.forbes.com/sites/anthonydemarco/2020/10/01/new-book-reveals-the-stories-behind-the-worlds-most-innovative-jewels/?sh=49fddf5d517e

Written by Anthony DeMarco, Senior Contributor for Watches & Jewelry on 1st October 2020.